Way back in the 20th century – remember that century? – I was an editor at The Tampa Tribune – remember newspapers? – and I hired a young man named Kurt Loft, to cover The Florida Orchestra and other classical shows in the new performing arts complex that is now called the Straz Center.

Kurt was still a student at the University of Florida but nobody knew classical music like Kurt. He went on to have a stellar career at the Tribune and continues to write about his favorite subject for national magazines, for the Florida Orchestra itself, and for the Palladium.

For the past several years, Kurt has written the program notes for the Palladium Chamber Players series. This year is no exception.

The Players return to our stage on Wednesday, Jan. 17, at 7:30 p.m., with a program featuring the works of both Robert and Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms. For tickets and more information, you can follow this link.

Kurt’s notes are in our printed program, but I thought it would be good to give you a headstart on the concert by featuring his commentary in my blog:

Palladium Program Notes – January 17, 2024

By Kurt Loft

The Chamber Players perform Schumann and Brahms

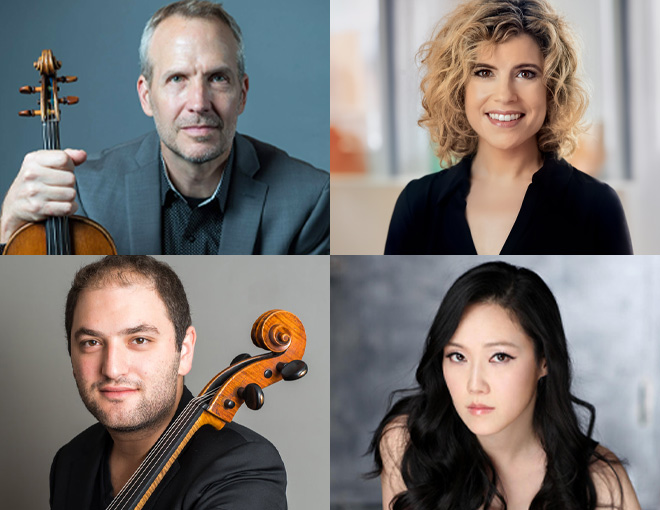

Jeffrey Multer, violin

Danielle Farina, viola

Julian Schwarz, cello

Jeewon Park, piano

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Märchenbilder, Op. 113

I. Nicht schnell

II. Lebhaft

III. Rasch

IV. Langsam, mit melacholischem Ausdruck

Danielle Farina, viola; Jeewon Park, piano

The first half of tonight’s program features three duos with the piano teaming up with viola, violin, and cello, respectively. It opens with Märchenbilder, or Fairy Tale Pictures, a set of four-character pieces for viola and piano that expresses the composer’s talent for meticulously crafted miniatures.

Although Schumann left no clues about what each piece is about, listeners can decide for themselves if they involve goblins, elves or sprites – or simply a bit of intangible imagination. The pictures were so successful that five years later Schumann composed a sequel, Märchenerzählungen, or Fairy Tale Narrations, for clarinet, viola, and piano.

The pictures can be described as sweet, charming music, balancing innocence with nervous energy – qualities we associate with Mendelssohn. The opening movement, Nicht schnell (not fast), is sad and melancholy, the viola’s long lines singing above a tender but incisive keyboard part. The next section, Lebhaft (lively), begins as a fanfare fueled by percolating rhythms and a series of spirited melodies.

True to its tempo marking, Rasch (quickly) moves forward on a sixteenth-note pattern passed between the two instruments before settling into a calming middle section. The concluding Langsam, mit melancholischem Ausdruck (Slow, with melancholy expression), assigns a lovely tune to the viola above sonorous playing from the keyboard. It all ends on a happy note, as fairy tales often do.

“I love Schumann and am so excited to be playing this piece with Jeewon,’ says Danielle Farina. “Schumann’s music has such a breadth of emotion and beauty, and this piece is one of my favorites.’’

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Three Romances, Op. 22

I. Andante molto

II. Allegretto

III. Leidenschaftlich Schnell

Jeffrey Multer, violin; Jeewon Park, piano

For centuries, classical music was akin to a private men’s club. Yes, many gifted performers and composers in the past were women, but the male monopoly and misogyny into the 20th century didn’t exactly inspire female musicians to take up the baton, so to speak.

Clara Schumann was a rarity. Born in 1819, she may best be remembered as the wife of the composer Robert Schumann but could well have mirrored his acclaim had history given women more artistic latitude.

“I once believed that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea – a woman must not desire to compose,’’ she wrote. “There has never yet been one able to do it. Should I expect to be the one?”

Those expectations certainly have changed. Today, women hold positions in every aspect of the classical arena, and many believe Clara helped break ground, especially in the development of the piano recital and its programming. Clara also made her mark in chamber music, including the Three Romances you will hear tonight, which reflect the new Romantic school of its time through innovative harmonies and rhythms and freedom of form.

The first, marked Andante molto, opens with a yearning, almost tragic-sounding melody on the violin, the piano rumbling its support from below. A series of bright arpeggios follow, then a quote from her husband’s First Violin Sonata.

The next section is a fragrant, tightly wound allegretto, a sort of musical palate cleanser to set up the finale, which the composer titled Leidenschaftlich schnell, or “passionately fast.’’ After an extended dance between the two instruments, the violin’s long lines embrace the rippling piano, and both end their duet on a soft note. In reflection, listeners are left with a sense of peace, like a world in balance.

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Adagio and Allegro in A-flat Major, Op. 70

Julian Schwarz, cello; Jeewon Park, piano

The Palladium musicians return to Robert Schumann with the rarely heard Adagio and Allegro, a brief work that puts in motion the contrasts in the composer’s personality. A prolific and imaginative writer and critic, Schumann created imaginary characters to represent his ideas, including the dreamy Eusebius and the exuberant Florestan.

While these were more literary than musical figures, they could easily have steered the emotional extremes of this character piece. Originally written for horn and piano, this version for cello delivers a deep, earthy texture, and the piano is never subordinate to its partner – the two are equals from the start.

The work in many ways captures Schumann’s emotional “longing for the infinite,’’ how the German writer E.T.A. Hoffman summarized the undercurrent of the Romantic age. The two sections are set apart but bonded by a quiet urgency, and the composer’s wife, Clara, called the music “splendid, fresh and passionate,’ balancing tenderness and virtuosity.

The adagio unfolds as a long sigh, one of Schumann’s most fervent creations, and the two instruments embrace in a tightly coordinated dialog throughout. The pace quickens in the allegro, marked “fast and fiery,’’ the piano in full harmonic support of the cello’s temperamental, quick-fingered phrasing and restlessness.

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor, Op. 25

I. Allegro

II. Intermezzo. Allegro, ma non troppo – Trio. Animato

III. Andante con moto

IV. Rondo alla zingarese. Presto

Brahms’s reputation as a composer for orchestra often overshadows his efforts in the realm of chamber music, but much of the latter is symphonic in concept. The Piano Quintet in F minor, the B-Flat Major String Sextet, and even the Horn Trio sound like exquisitely crafted miniature orchestras. The macro and micro compositions of Brahms also share another trait: both are built on the classical scaffolding of Haydn and Mozart, yet express the emotional ideals of the new musical age that followed.

This was no easy task, yet Brahms fused these elements into his own personal style. He was all at once a romantic classicist, classical romantic, neo-Baroque adherent and Renaissance polyphonist, notes Jan Swafford in his 1997 biography on the composer: Such a synthesis, he writes, “should not have worked, but he made it work.’’

Brahms liked to compose music in pairs and sketched the A Major and G minor Piano Quartets alongside one another, and both earned him among the adoring Viennese public the reputation of “Beethoven’s heir.’’ This multi-tasking style may have been how Brahms played ideas off one another and channeled them in the right direction.

For a chamber work, the quartet you will hear tonightis massive – as long as any of his symphonies – and opens with a remarkable inventiveness in the way two contrasting themes interact over nearly 15 minutes. Brahms wrote the delicate second movement as a love letter to Clara Schumann, and after hearing it, she wrote back: “it is as if my soul were rocked to sleep on the sounds.’’

After an expressive andante, Brahms concludes with an upbeat “Rondo in the Gypsy Style,’’ not unlike the ending of his own Violin Concerto. This exciting section makes use of four folk themes that come together in an irresistible dance between piano and strings, with a coda designed to bring down the house.

Arnold Schoenberg, one of the most influential composers of the 20th century, was so impressed with the sonorities of this work that he made an arrangement for a modern orchestra − more than 75 years after its premiere.

Leave a Reply