In advance of our Palladium Chamber Players concert on Wednesday, April 12, classical music writer (and chamber music lover) Kurt Loft interviewed violist Danielle Farina, who will be performing a solo work by Bach that night.

The concert, which features our entire Palladium Chamber Players ensemble – Jeffrey Multer, Jeewon Park, Ed Arron and Danielle – will be also performing works by Richard Strauss and Camille Saint-Saens. For tickets and more information call our box office at 727 822-3590 or follow this link for online tickets.

Here’s Kurt’s preview with focuses on Bach’s Suite No. 1 in G Major:

By Kurt Loft

When Johann Sebastian Bach died in 1750, he was little known outside his native Germany, and many of his more than 1,125 surviving works fell into obscurity. Unlike his contemporary, George Friderick Handel, who enjoyed fame all over Europe, Bach mastered his art in relative quiet and wore the moniker of a composer of old fashioned music.

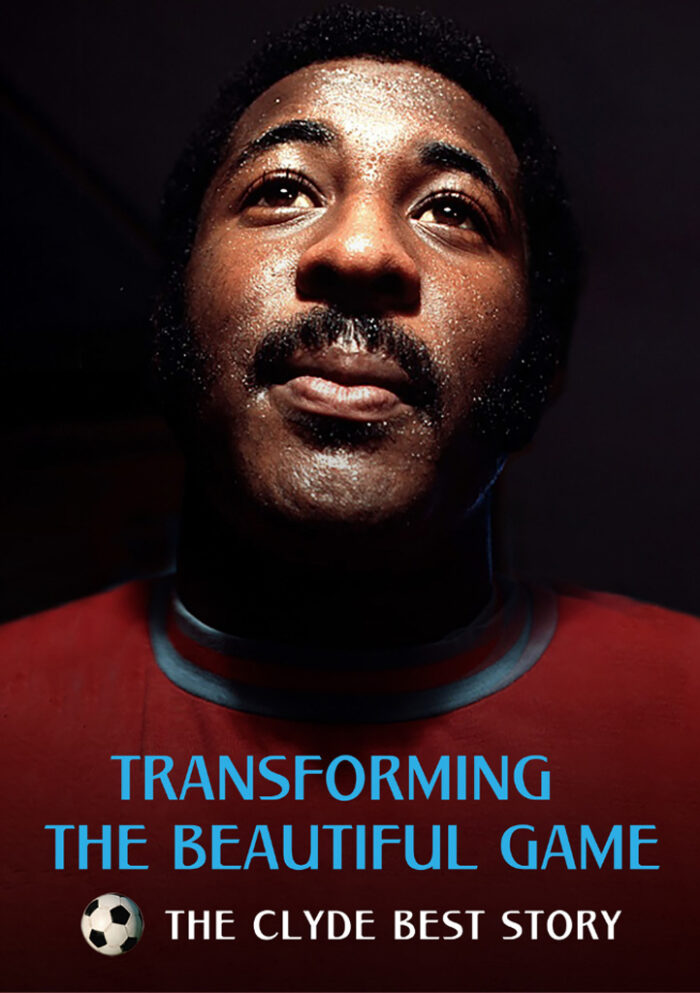

Danielle Farina

Today, it seems inconceivable that Bach would be ignored for nearly a century. By the mid-1800s, evidence continued to surface that would form one of the greatest bodies of work by any artist, a crowning exploration of style, form, and expression undiminished by the passage of time.

From the breathtaking spirit of his Masses, Passions and sacred works to the contrapuntal puzzles of his fantasies and fugues, Bach achieved a level of consistency that defies lumping his life’s work into early, middle, and late periods. A seriousness of purpose underlines everything he composed –he lived for the ‘’glory of God and refreshment of the soul’’ – spanning the grandiose creations for chorus and orchestra to the simplest utterance for a single instrument.

On April 12, the Palladium Chamber Players pay tribute to the latter with a rarely heard treatment of one of the Six Unaccompanied Cello Suites – considered the Holy Grail for any cellist. This performance, however, features the Suite No. 1 in G on the viola, not the cello, moving everything up to the alto range and creating a lighter soundscape.

“It’s written for cello but the only difference is the viola is just an octave higher,’’ said violist Danielle Farina, who performs the Bach. “But it takes on a different character and that affords you to use different tempos as a result, so it can be slightly faster.’’

Farina will play the seven-movement suite as the program’s centerpiece, and joins pianist Jeewon Park, violinist Jeffrey Multer, and cellist Edward Arron in Richard Strauss’s Three Pieces for Piano Quartet and Camille Saint-Saens’s Piano Quartet No. 2 in B Flat. In the Bach, Farina will be on her own, with no colleagues to lead or follow. This means she can be utterly creative.

“The Bach suites are difficult technically because there’s so much nuance if you choose to see it,’’ she said. “I love the fact that you can delve into the music and create your own interpretations. There are an infinite number of interpretations with all of the suites, which is what makes them so rewarding.’’

The Six Suites for Unaccompanied Cello remain among the supreme works for a solo instrument, prized as much for their technical sophistication and originality as their intimacy. Composed over six years beginning in 1717, the suites pose a formidable challenge in technique and emotional range for the most skilled performer, one reason the late Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich called them “the most precious music in the world.”

The Suite No. 1, like the rest, is cast in the model of the French suite of the time, and begins with an expansive prelude, followed by a series of dances: an allemande, courante, sarabande, a pair of menuetts, and a closing gigue.

As a whole, the music “suggests” a running melody by placing multiple voices sequentially. With the cello, its curved placement of strings doesn’t allow for traditional chords; it can only create the illusion of multiple voices. So Bach alternates one melody with another to “fool’’ the listener into hearing two or more lines simultaneously, creating a sort of musical hologram.

Technical issues aside, Bach is really about the spirit. His mathematical structures serve a higher purpose.

“When you talk to any musician about Bach, they will tell you he’s satisfying on a very deep level,’’ Farina said. “His compositions are perfect in most every way, and when you add the emotional component, he speaks to so many different people on some many different levels. He’s also fun to play, so that makes for a perfect equation. I’ll never tire of playing Bach.’’

###

Leave a Reply