The Palladium Chamber Players return on Wednesday with another exciting evening of music.

The concert features three of our core players, including artistic director Jeffrey Multer, plus two special guests. Along with Jeff on violin, the players are: Derek Mosloff, guest viola, Edward Arron, cello, Jeewon Park, piano and Ryan Sujdak, guest double bass.

For tickets and information, please follow this link.

Kurt Loft wrote a preview of the show for our program. It appears below.

See you at the concert!

Wednesday’s show aims to be ambitious and surprising

By Kurt Loft

This week’s concert by the Palladium Chamber Players might be called conservatively ambitious, with well-worn music that still manages to surprise, and will stick to your ribs as you leave the hall. That’s what good programming is all about, and Jeff Multer, the group’s artistic director, gets a gold star for this installment of the season’s lineup.

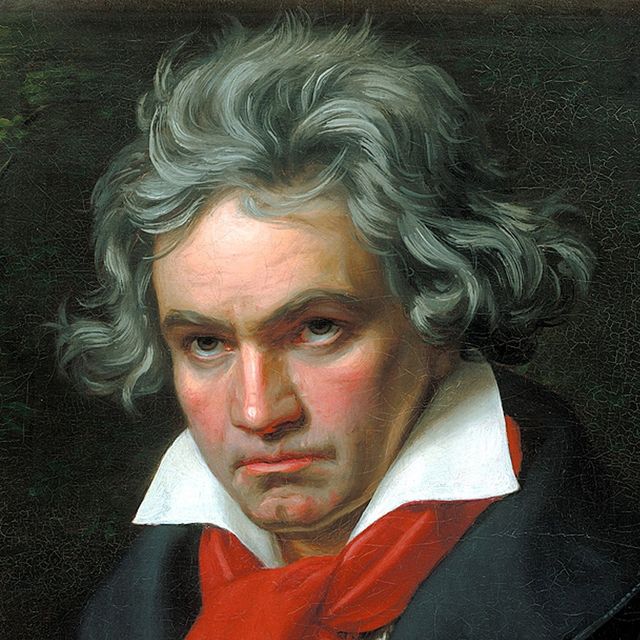

For Beethoven buffs, the night begins at the beginning, featuring the composer’s nascent Piano Trio in E-flat Major, Op. 1, No. 1. Note those numbers: the first of the first opus, so you’ll be hearing among the earliest of Beethoven’s roughly 725 published compositions.

Although cast in the refined classical-period mold of Haydn and Mozart, the trio develops through four movements as more than entertainment, with virtuosic flourishes that predate Beethoven’s middle-period piano sonatas.

The piece opens with an ascending figure known as the “Mannheim Rocket,’’ a technique used by musicians of the Mannheim school to inject brilliance into a phrase. This 10-minute allegro undergoes a variety of twists and turns in developing a second and third theme before introducing a lovely adagio cantabile. Beethoven follows with a spirited scherzo, the piano and strings cajoling like children at a playground. The finale is all lighthearted, with another rocket launched to end the trio in high spirits.

Fast forward more than 150 years and we arrive at the Sonata in C Major for Cello and Piano, Op. 119, by Sergei Prokofiev, a 20th-century original with a unique sonic signature that oozes from this piece. He spent two years tweaking the score, finishing it in 1949 with valuable suggestions from the great Russian cellist, Mstislav Rostropovich, to whom the work is dedicated.

The cellist gave the first performance of the work in 1950, alongside pianist Sviatoslav Richter. But the duo first had to play it for the Soviet censors, who would decide its fate. In his memoirs, Richter wrote: “They needed to work out whether Prokofiev had produced a new masterpiece or a piece that was ‘hostile to the spirit of the people.’ ‘’

The lengthy opening movement begins with the cello growling in a low voice, and soon the two instruments embark on a sunny, uplifting theme. A brief middle movement seems almost torn from a page of Haydn, lyrical and witty, a musical palate cleanser.

The finale is full of pizzicatos and rhythmic twists that makes us wonder if Prokofiev was pleasing himself or the censors, and the music ends with a series of powerful piano chords and the cello fading away on an open C string.

The night’s gem is the Piano Quintet in C minor by Ralph Vaughan Williams, whom we seldom hear in a chamber setting.He twice revised his original score of 1903, but then it fell either out of favor or simply was forgotten. It wasn’t published until 2002 – nearly a half century after the composer’s death.

The big opening movement announces itself with a sharp attack by the group, then immerses us in dense, orchestral textures reminiscent of Brahms (Vaughan-Williams would roll over in his grave at such a comment, as he was not a fan). The marking con fuoco underscores the passion that drives this section.

The relaxed middle movement uses the tune from Silent Noon, a song written by the composer about the same year, and exploits the range of the strings as they percolate among the piano’s delicate fingerings. The finale unfolds in variation form, the main theme undergoing five distinct twists before the work ends in repose.

Leave a Reply