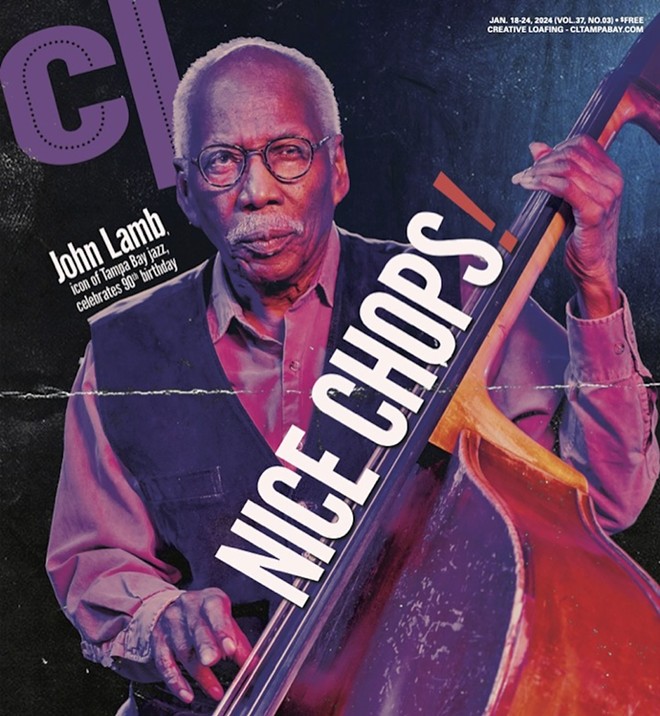

John Lamb’s actual birthday is in November, but when you reach 90, you should be able to celebrate all year.

At the Palladium, where John is still an active player in our jazz shows, along with a donor and fan, we are celebrating his milestone birthday on Saturday, Jan. 20, at 8 p.m., with a concert featuring a host of Tampa bay jazz stars.

Tickets are selling fast for this show. To get yours, please follow this link.

Lamb himself will perform with his longtime friend and collaborator, Nate Najar, and will be part of a few other ensembles. He’ll also pick up the 2024 Palladium Jazz Award, that I’ll present to him at the top of the second set. The award was designed by Richard Logan, a Clearwater-based glass artist.

Personally, I love John and am proud to count him as a friend and mentor. At the Palladium, we love celebrating John and his accomplishments, including his stint as part of the Duke Ellington Orchestra. We staged a concert for his 80th birthday and celebrated his 85th.

I could tell you a lot more about John, but I don’t have to. Creative Loafing’s Eric Snider interviewed John for this week’s cover story for the publication. That story is printed here. To read it at the Creative Loafing site, please follow this link.

Bay area jazz legend John Lamb talks Duke and more, before 90th birthday concert

By Eric Snider

Creative Loafing

1-16-24

Photo by Steve Splane. Design by Joe Frontel

If you go to shake John Lamb’s hand, be ready. I did just that on a Thursday afternoon in early January, having concluded an hour-long interview in his waterfront home in far south St. Petersburg. I extended my right hand. He took it. I squeezed a little harder than usual, a test. Lamb gave me a mischievous smile—and clamped. His handshake did not bring me to my knees, but it was clear who had the far stronger grip. And Lamb could’ve been holding back.

This was not the hand of your average nonagenarian. John Lamb turned 90 on Nov. 29. Spending some 70 of those years playing the bulky acoustic bass, working those thick metal strings, will give you strength. Lamb stopped gigging when the pandemic hit and he no longer takes jobs. But I expect he’ll play some this weekend when a roster of top local musicians will pay tribute to him in The Palladium’s Hough Hall.

Lamb let me in the front gate of his ranch-style home, clad in baggy jeans and a gray, long-sleeve shirt, his head topped by a gray baseball cap. His teeth were preternaturally white. As an icebreaker, I asked Lamb how he was feeling, being 90 and all. He responded, cryptically, “I just turned. I’m getting used to being 90.”

I had hoped to sit back in an easy chair while Lamb regaled me with stories about his celebrated musical career, about the musicians he’d share stages with—most notably three years in the mid-1960s as part of the Duke Ellington Orchestra, which was chock full of fabled players. Instead, Lamb ushered me from room to room, sitting briefly, pausing to point out framed photos (including two with Duke) and other mementos.

He stopped at a chocolate-brown bass perched on a stand in his living room and played a short, swinging line. “People don’t walk the bass like that anymore,” he said. Lamb moved to a nearby upright piano. “I’m not a piano player, but I learned this,” he said, and tickled out a riff he picked up from stride piano titan Willie “The Lion” Smith.

The bassist’s reminiscences came in compact, staccato packages, capped with hearty laughter. “Met [Charles] Mingus once,” he said of the iconoclastic bassist/composer whose modern jazz sound contrasted with Lamb’s swing-based style. “They told him I was Duke’s new bassist. Mingus paused and said, ‘You play your bass, man.’” After a laugh, Lamb added, “It was complimentary.”

Another—about sitting in with the legendary trumpeter Miles Davis: “[Pianist] Red Garland, who I had done some gigs with, says to Miles, ‘I want to introduce you to a bass…” And here Lamb leaned in close, lowered his voice. “Miles says, ‘you got a smoke on you?’” More laughter.

It’s interesting to note that these and a few other recollections involved jazz legends of the post-Swing era. From 1964-1967, Lamb was part of a 16-piece ensemble playing tightly structured arrangements, while legends such as Miles, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman and others were leading small units, cutting loose and reshaping jazz. I posed this idea to Lamb and asked if he ever felt he was missing out?

“Missing out on what?” he asked.

“All the new stuff that was happening, the freedom,” I replied.

“Oh, no, man. Music is just music,” Lamb said. “I never would have had the other experiences with other people if it had not been for Duke.”

Nevertheless, I found it difficult to get much from Lamb about Ellington, arguably one of the half-dozen most important musicians of the 20th Century, regardless of genre. Lamb did not wax rhapsodic about being on the bandstand night after night with a pack of other world-class musicians playing the Ellington songbook, which was etched in the American psyche.

I asked Lamb what Duke was like as a boss. “He’d get frustrated [on stage] sometimes, you know. He’d bang on the piano keys,” Lamb recalled. “[Trombonist] Lawrence Brown told me, ‘Whenever he does that, just turn your head to him and smile.’ So I did that. I never argued with Duke. I really didn’t dig into his feelings because he was the old man; he paid the checks.” (When Lamb joined at age 30, Ellington was 65.)

Lamb recalled hanging out with the boss once. “It was Louie and him and myself,” he said, referring to the drummer Louie Bellson, “And [Duke] invited me up to the front of the plane. He says, ‘come on up and have a bite with us.’”

Lamb played five or six nights a week with the big band. He and Bellson backed Duke when he did guest appearances with symphony orchestras. Lamb handled bass duties on nearly 20 Ellington albums, studio and live, a few of them significant. You can hear Lamb confidently laying down a slippery line beneath Paul Gonzalves’s languid tenor saxophone on “Tourist Point of View,” or playfully sparring with Ellington’s piano on “Ad Lib on Nippon,” both from Far East Suite. Throughout that classic 1967 album, Lamb’s time and tone are sturdy, and he navigates the complex arrangements with swagger.

During the Duke years, the money was good—for the times. After he got the surprise call from Ellington, passed the audition and signed on, Ellington’s son Mercer, who ran the business side, told Lamb he’d be paid union scale.

“That was around $65 a night,” Lamb recalls. “I was working at Acme Market in Philadelphia making about $45 a week. Of course I had to go on the road with Duke.”

Lamb did not drink, smoke or do drugs, one of the reasons he sidestepped the cliques that tended to develop among large groups of musicians on the road. His closest friend was clarinetist Jimmy Hamilton, another non-drinker. Lamb said he sent most of his money home to Philadelphia, where his wife, Paula, lived with their son and daughter.

I asked Lamb how he came to leave Ellington’s employ. “There was another part of my life other than being a musician,” he said. “I decided that my family was most important.”

Florida born, world-class

Lamb started out a Floridian, growing up in Vero Beach and Fort Pierce. His first exposure to music was in church, where “my cousin Mary, she used to sing and every time she sang she fainted,” he said. “I remember they used to carry her out of the church. So all that was in me.”

Lamb’s father died when he was four or five, and his mother remarried. The young Lamb took piano lessons, then gravitated to the tuba, which he played in the high school band. I asked him if the family was consigned to the Black section of town. “You know what, when I was a kid it didn’t make a bit of difference to me what section of town I lived in because the man that raised me had four houses that he owned and I used to clean them up before I went to school,” Lamb said, his voice rising.

I replied, “But we hear those stories about Black kids not being able to swim in the town pool. Did you experience any of that kind of stuff?”

“I couldn’t swim anyway, so what was I worried about swimming in somebody’s pool for?” Lamb replied. “I had friends that I played with at school every day. What they did on their side of town, that’s their business. There were restrictions in the white community, restrictions in the Black community. I had restrictions at home. I didn’t have that hangup, man.”

Unscarred by racism, Lamb signed up for the Air Force at age 17, immediately after graduating high school. He joined the military band. While stationed in Great Falls, Montana, the bandmaster offered him the chance to sub for the string bass player. Lamb winged it well enough to take over the job permanently. And he did what it took to get good. “One time, I practiced all day and then half the night,” he said, laughing.

In the barracks, the airmen listened to a lot of Stan Kenton and Woody Herman, two white bandleaders known for their brash, brassy sounds. Then, “One night, I was listening to the jukebox, and I heard this guy, he had this big [bass] sound.” Lamb recalls. “I asked one of the guys, ‘Who is that?’ It was Ray Brown with Oscar Peterson.”

Hearing some lean piano-trio music, with bass work by a legend, proved revelatory. After his three-year Air Force stretch, Lamb started gigging in Philly and Boston, working with pianists like Jaki Byard and Garland, as well as short stints with such singers as Ella Fitzgerald and Carmen McRae. One night, when Lamb was jamming at an after-hours club, Billie Holiday came in carrying a dog in her purse, Lamb recalled: “A guy introduced me, I said hello. I reached down to touch the dog and it snapped at me.” Lamb said, chuckling. “She said, ‘No, not like that honey, put your hand like this.’ I think Billie sat in for a tune.”

Then came the call from Duke, and Lamb heeded it.

Post-Duke, ‘Burg-bound

In ‘67, when it was time to head back out on the road, Lamb informed Ellington that he planned to go to school, effectively resigning. The bassist earned a degree in music education from the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. Then, “I taught a few years in Philadelphia and came down to St. Pete,” he said. “I knew nothing about St. Pete. I was looking around in Sarasota. I came here because my wife had some people here.”

I wondered if, after seeing the world, playing for ecstatic audiences, and living in bustling Northeastern cities, Lamb found St. Pete to be a sleepy town. “I didn’t think about it that way,” he explained. “I’d been everywhere with Duke. I thought about the people I met here and how cordial they were. And we had musicians here too, you know.”

One of them was trombonist Buster Cooper, a former Ellington bandmate, who’d moved back to his native St. Petersburg. “We used to play in Buster’s sister’s backyard, little parties and stuff,” Lamb said. “We got tight again.” Cooper died in 2016 at the age of 87.

Lamb laid down roots—for good. He taught bass and music at Seminole High School. He sold life insurance for a spell. Chris Styles, the first Black chair of the music department at St. Petersburg Junior College (now St. Petersburg College), hired him to give bass instruction.

Lamb became a stalwart on the local jazz scene, and rarely if ever ventured beyond it. He gigged steadily at hotels on the beach, in restaurants, as the house bassist for the jazz club at the Tierra Verde Island Resort in the early-1980s, supporting the likes of trumpeter Clark Terry and vibraphonist Milt Jackson. “Because I didn’t drink, I could play at night and get up in the morning to go teach,” he said.

Lamb was in demand for his clean, muscular sound and impeccably articulated notes. “People are consuming the sounds, the vibrations of air,” he asserted. “They’re part of the thing. I didn’t want them to necessarily look at me. I wanted them to feel what’s there. I was just a vehicle.”

I checked my watch. I’d been in Lamb’s home for a little over an hour. It seemed an appropriate time to leave. That’s when I extended my hand and got clamped. I shook it out a little as I headed for the door.

Leave a Reply