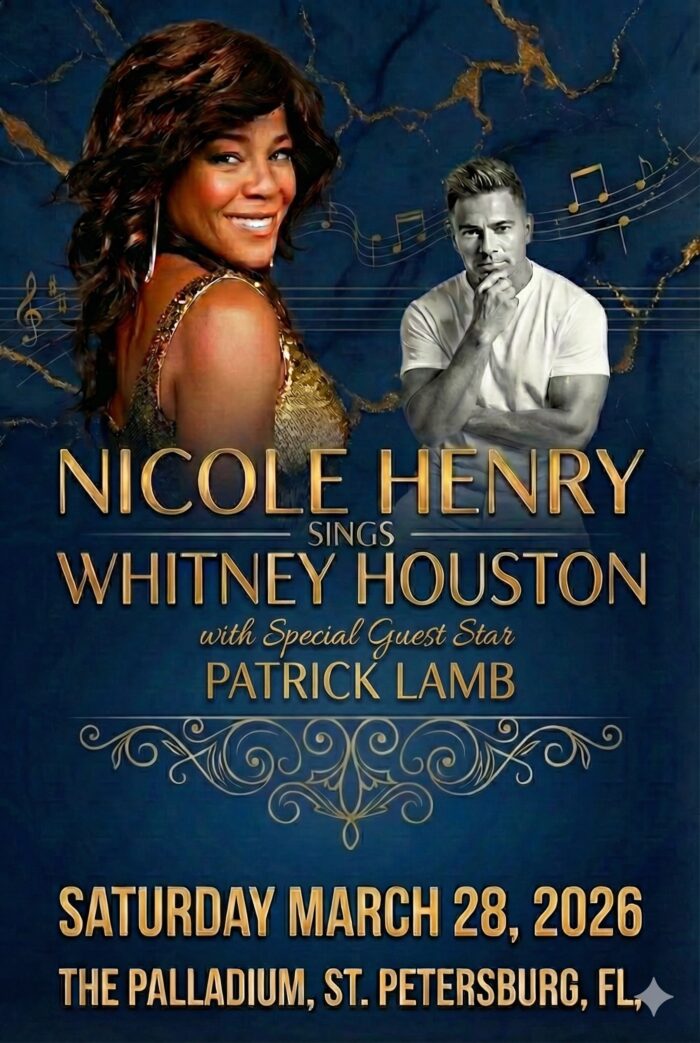

Channeling a Bombshell, One Jazzy Note at a Time

By JOHN MARCHESE/New York Times

AS a teenager watching old movies on television, Harry Allen heard Marilyn Monroe speak to him.

“I have this thing about saxophone players,” she said in her famously girlish and breathy style. “Especially tenor sax.” She added: “All they have to do is play eight bars of ‘Come To Me, My Melancholy Baby,’ and my spine turns to custard. I get goose-pimply all over, and I come to ’em.”

Decades after hearing those words Mr. Allen, 44, is a well-established figure in jazz, performing around the world and recording prolifically — on tenor sax. “That line,” he said recently, paraphrasing Monroe, “all a saxophone player has to do is play ‘Melancholy Baby,’ and I’m his. That made me really want to become a saxophone player.”

The lines come from the 1959 screwball comedy “Some Like It Hot,” in which Monroe played Sugar Kane Kowalczyk, the singer with an all-female swing band (all-female, at least, until Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis join up disguised as women). In the film Monroe performs several songs, including a heartfelt rendition of the standard “I’m Through With Love” and a near-novelty take on “I Wanna Be Loved by You.” They are part of a body of recorded vocal work she left behind that some, like Mr. Allen, believe is overlooked and underestimated.

“Obviously,” Mr. Allen said in a phone interview, “she is considered an icon, but mostly for being maybe the most beautiful and sexiest woman ever. I’ve always thought that Marilyn Monroe was a really fine singer. Today she’d be considered one of the best singers around, if she were here.”

Mr. Allen is such a supporter of Monroe’s music that on Tuesday he begins a five-night run at Feinstein’s at Loews Regency with a show titled “Some Like It Hot — The Music of Marilyn Monroe,” featuring his working quartet joined by the vocalist Rebecca Kilgore. When Mr. Allen contacted her about the concept, Ms. Kilgore said her first thought was, “I can’t possibly impersonate Marilyn Monroe.”

Many other performers have mimicked Monroe in various ways, from Madonna’s music video homage to “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” to drag show performers around the globe. James Franco even gave it try while hosting this year’s Oscars ceremony. But Ms. Kilgore had something else in mind.

“I had to get rid of the concept of having to inhabit her persona,” she said by phone from her home in Portland, Ore., “which is kind of born from the cabaret world, which I’m not really a part of. I decided to have fun with the music.”

As she started studying Monroe’s recordings, tracking down movie soundtrack albums and compilations to prepare for the show, Ms. Kilgore soon realized that there wasn’t a large collection of material, fewer than three dozen songs in all. The actress sang in 10 movies, starting with a solo turn on “Anyone Can See I Love You” in the 1948 film “Ladies of the Chorus” and concluding with several numbers in “Let’s Make Love,” in 1960, in which Monroe sang duets with Yves Montand and Frankie Vaughan and stepped out to solo on the title song and Cole Porter’s “My Heart Belongs to Daddy.” Unsurprisingly, throughout her film career as a vocalist, the sex appeal seems as important as the singing.

“That on-screen persona was the only one that I knew,” Ms. Kilgore said. “Even watching her movies as a young girl I found her sexy, but not in a threatening way. She was wise, pretending to subjugate herself to men, but doing it with a wink, as a kind of game she was playing.” Now, often focusing only on the audio, the singer found something else in Monroe’s performances.

“It’s absolutely compelling the way she inhabits the material,” Ms. Kilgore said. “It’s hard to put into words. It’s very mysterious. Some people sing a song, and it’s pretty, but you never want to listen to it again. Marilyn just bears repeated listening.”

Gary Giddins, the jazz critic and biographer of Bing Crosby, performed his own reassessment of Monroe’s musical ability and was impressed. “She had the same problem as Fred Astaire,” Mr. Giddins said in a telephone interview. “They were both wonderful singers, but you don’t think of them as singers. So much of Monroe is the way she sells the song. You expect her to be second rate, but she never is.”

As Ms. Kilgore began practicing the songs she would include in the show, she constantly fought the tug toward imitation. “I would find myself doing that pouty, come-hither wispy style that’s so easy to imitate,” she said. “I had to keep telling myself that I’m not going to imitate her. I’m going to do a — quote, unquote — jazz singer’s interpretation.”

In 1953, as Monroe was preparing for the film “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” which would produce her memorable performance of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” she was advised by a musician that repeated listening to a jazz singer would be the key to her own development as a singer.

“In the very beginning,” said Hal Schaefer, a jazz pianist, composer and arranger who was hired as Monroe’s vocal coach, “I told her to buy Ella Fitzgerald’s recording of Gershwin songs. And I ordered her to listen to it a hundred times.”

“She wasn’t really into jazz when she came to me,” Mr. Schaefer added, by phone. “But I told her: ‘Look, I’m going to be your guide. This is where we have to start: listening to the best female singer there is.’ ”

The actress became a fan of Fitzgerald, and the two women became friends. In 1955 Monroe persuaded the owner of the Mocambo, a popular Hollywood nightclub, to lift its policy of not booking black performers and hire Fitzgerald. Monroe reportedly promised to attend every performance seated at a front table. Years later Fitzgerald told Ms. Magazine, “I owe Marilyn Monroe a real debt.”

Monroe’s artistic debt to Fitzgerald is harder to pinpoint. Though the actress would develop a reputation for being difficult to work with, often showing up late on set or not at all (she was fired from her last film for repeated absences), she worked conscientiously on her singing, Mr. Schaefer remembered. “About 50 percent of what she became as a singer she had to begin with,” he said. “Her intonation was good, and her time was good.” Working in a bungalow studio, he would guide Monroe through exercises to expand her vocal range and to work on breath control.

When a writer from Collier’s magazine visited Monroe and Mr. Schaefer at work one day in 1954, the actress told him, “I won’t be satisfied until people want to hear me sing without looking at me.” But she quickly added, “Of course, that doesn’t mean I want them to stop looking.”

Mr. Schaefer became so impressed with his student’s progress, he said, that he persuaded executives at RCA Victor to record her singing two songs with nobody but the backup musicians looking at her and no film performance to pair the vocals with. The 1954 session was not immediately released. It produced “A Fine Romance,” the Jerome Kern-Dorothy Fields tune, with a spirited jazz arrangement by Mr. Schaefer and Monroe swinging in the lower portion of her vocal range. Not Ella, but headed in that direction.

The B-side was a ballad called “She Acts Like a Woman Should.” On it Monroe shows a firm command of phrasing and avoids the sexpot styling that dominates so many of her other recordings. “If you hear the record now,” Mr. Schaefer said, “there’s no baloney about it. She’s a real singer with a big band in a studio, not some movie star they’re trying to pass off as a singer.”

When Ms. Kilgore was surveying Monroe’s work, she was drawn to that song despite some seriously retrograde lyrics. “I didn’t have any indelible visual to try to divorce myself from,” she said. “That’s been the most difficult aspect of preparing for this show. I also like the performance because it seems to have less of that self-conscious sex-selling attitude. It’s more natural, honest and very appealing.” She will perform the song at Feinstein’s.

The one tune that will not be included in Ms. Kilgore’s show is perhaps Monroe’s most famous singing performance, and her last. In 1962, three months before she died, Monroe appeared at Madison Square Garden for a party honoring President John F. Kennedy on his 45th birthday. The jazz pianist Hank Jones, her accompanist that night, later told an interviewer for NPR that they rehearsed eight hours to prepare 16 bars of music.

The result, a strange, halting and almost absurdly breathy and flirtatious performance of “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” seems now like Monroe doing a parody of herself, and it is often imitated. The indelible impression left by the 30-second performance goes a long way toward overshadowing all the solid singing Monroe had done in the decade before.

So this week at Feinstein’s, as Mr. Allen and Ms. Kilgore salute Monroe’s music, even if an audience member is celebrating a birthday, Ms. Kilgore will not sing “Happy Birthday.” But there’s a chance that Mr. Allen could be persuaded to play eight bars of “Melancholy Baby.”

For tickets and more information visit www.mypalladium.org or call the box office at 727 822-3590.

Leave a Reply