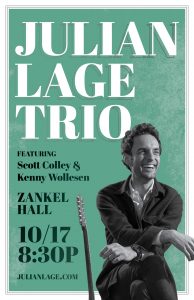

Along with our slate of the best regional jazz and blues artists, we like to spice up the Side Door lineup with top touring artists. And one of the best young players in jazz – Julian Lage – fits that bill.

He just recorded an album with the jazz pianist Fred Hersch (who sold-out the side door two years ago) and just played Zankel Hall – a theater within Carnegie Hall – with this trio. This Sunday, Nov. 15, you get to hear Lage and his trio in the intimate Side Door Cabaret.

Julian Lage

To get you excited, check out this New Yorker magazine story about Lage and guitarist Chris Eldridge, that appeared last year. It was written by one of my favorite New Yorker writers – Alex Wilkenson.

And come and join us at the concert this Sunday at 7 in the Side Door. For tickets and more info, follow this link.

To read the entire New Yorker story, follow this link.

OCTOBER 16, 2014

Good Guitar

BY ALEC WILKINSON

The New Yorker Culture Desk

Poster from Lage’s Carnegie Hall show

The other night, a rainy night, I went to hear the superlative guitarists Julian Lage and Chris Eldridge, who were playing in a small, glass-walled room at the top of the Standard East Village, with the city in the mist behind them. Lage is a pantheist, known mostly for playing several kinds of jazz, in trios and quartets and by himself, and Eldridge is a member of the brainy, hot-shot string band Punch Brothers. The two of them made a record called “Avalon,” which came out last week, and the occasion was a launch party.

Lage and Eldridge aren’t the first two guitar players one might put together. Lage plays so many types of music, on both electric and acoustic guitars, that the list of possible associates is wide open for him, and Eldridge has colleagues among bluegrass stylists who might have come sooner to mind, players such as Bryan Sutton, for example. I’m not sure how they found each other, although there is a collection of musicians that includes Punch Brothers, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, the Milk Carton Kids, and Edgar Meyer, that verges on Lage’s territory, and both Lage and Eldridge live in New York.

Aside from their sensibilities and the elegant intelligence that each brings to the instrument, what makes their sound distinctive is that both are playing flattop guitars without amplification. Elderly Martins, from 1939, is what they are. Eldridge’s is a dreadnought, the largest flattop guitar, and Lage’s is a smaller version. Old acoustic guitars, if they are well-made, age handsomely. Their tones become as clear and specific as voices. The variable becomes what the musician can produce from them. Better hands produce more interesting remarks, that are spoken with better diction. The flattop guitarist most widely admired for his touch is Tony Rice, who is Eldridge’s mentor and who appears to be invalided out of playing from pain in his hands.

Eldridge grew up within the context of bluegrass. His father played banjo in a respected band, the Seldom Scene. He doesn’t play electric guitar, as Lage does. The guitar in bluegrass is traditionally a part of the rhythm section, partly because it is more difficult to play fast on a guitar than on a banjo or a mandolin or a fiddle. The frets are wider on a guitar, and the strings are heavier. The model of the bluegrass guitar player as soloist was introduced, in the nineteen-sixties, by Clarence White, who later played guitar with the country incarnation of the Byrds. Then it was refined by Tony Rice, whose guitar belonged to White. Early bluegrass guitarists kept to the base of the neck, the first position, and mostly they still do, but Eldridge, studying White and Rice, learned to play across the entire fretboard.

Guitarists who play fast in all genres are often resorting to patterns and repeating themselves. Sometimes this is the result of the pace; sometimes it is simply the result of an incurious mind. Jerry Garcia used to have his guitars strung with heavier than usual strings, to prevent himself from playing rhetoric. Eldridge has the technical command to play ideas rather than patterns. You can see him stumble sometimes as he searches to link one statement to another, but the hesitation is dramatic and only, at least for me, enlivens the performance.

The concert started with an intricate dialogue, chords strung between passages of double stops and single notes, something that sounded a little dreamy before committing to a discernible progression. For about forty-five minutes, the two of them played through a repertoire of country songs, ballads, a fiddle tune, and intricate instrumentals that they had either written or arranged. Lage’s knowledge of harmony and his familiarity with the fretboard is so extravagant and capacious that he brings flourishes to this music that it simply hasn’t enjoyed before. I thought I heard references, for example, to Charlie Christian and Chuck Berry and Jim Hall. Like David Rawlings, Lage sometimes seems to have a different route in mind from the obvious one supplied by the chord changes. His lines go farther and end later than you expect, and not always where you expect. His playing is cerebral, and sometimes playful, but, because his vocabulary is so expansive, it is also riveting: in his chancier attempts, he seems unsure himself of where he is going. An atonal passage appears suddenly and is used to bridge a moment between more regular ideas. He is in the highest category of improvising musicians, those who can enact thoughts and impulses as they receive them. This gives the music tremendous vitality, not only because the quality is rare but also because it is being brought to life in actual time—the performance is not simply a virtuoso recreation of the past. Lage is also visually arresting, because his left hand is like a tool. The fingers spread and move crablike up and down the neck or leap across strings and frets. It’s thrilling to see, although he makes no effort at stagecraft. He simply stands and plays.

Both Lage and Eldridge are lanky, and they wore dark, skinny suits, which seemed to frame the dark blond of the wood. Eldridge twitched and rose up on his toes and stamped his feet while he played, as if an excess of energy needed to be shed. He looked like a fidgety stork. His tone, even when he played quietly, was precise. Flattop guitars played too fast can sound more percussive than lyrical, especially in the mid-range, and he is one of the few guitarists who can preserve the pure, ringing sound. To Lage he played a generous and sympathetic second, offering ideas and support. Sometimes they chased each other, and sometimes they spoke like two men at a bus stop, comfortable with each other. Eldridge also sang a few ballads, including Gershwin’s “Someone to Watch Over Me.” He has a plaintive tenor, a little thin, which adds to its authenticity. He sings without artifice, and the lines come through as if confided. Listening to him I was reminded of how actors, especially Shakespearean actors, say that the ideal is to speak the lines as if they were occurring to you. On a couple of songs, Eldridge sang while Lage accompanied him, and the songs had a feeling of fleeting and fragile warmth.

“Avalon” was produced by Kenneth Pattengale, of the Milk Carton Kids. I happened to be standing next to him, and, now and then, on some of the country songs, he added a line of high harmony, just above a whisper, so it sounded in the darkness like something in church.

1 comment

Looks like a great show, thanks for the information.