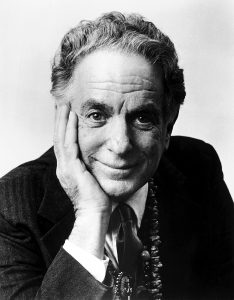

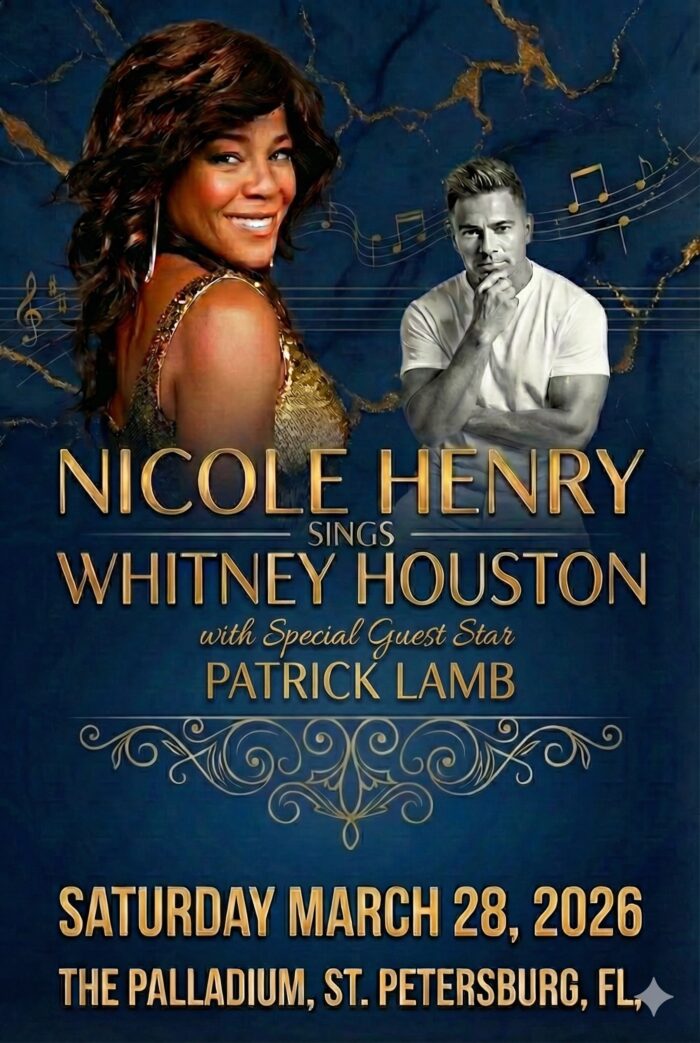

Paul Guzzo, of the Tampa Tribune, has written a wonderful story about David Amram, who appears tonight in the Palladium’s intimate Side Door Cabaret. Amram was a collaborator with many jazz and music greats, but he’s perhaps best known for his work with the beat writer Jack Kerouac.

Amram is performing with John McEuen, founder of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and another Amram collaborator. The show is part of a week of Kerouac related activities in St. Petersburg. It is also the kickoff the Palladium’s 15th Anniversary season.

You can read the full story by following the link below, or enjoy these excerpts.

http://tbo.com/events/kerouac-co-hort-to-join-fete-of-writer-20131017/

By Paul Guzzo

Tampa Tribune

Musician David Amram, who added jazz to the poetry of Jack Kerouac to create a duo that helped define the Beat Generation, will take part in two celebrations of his famous friend’s life this weekend in St. Petersburg.

Jack Kerouac

“The only people for me are the mad ones,” Kerouac wrote in his biographical novel “On the Road,” and Amram surely qualified.

He and Kerouac met in 1956 and instantly formed a creative partnership — Amram providing the music and Kerouac the words during presentations that still inspire the beat performances popular in coffee houses and clubs.

They remained close friends until Kerouac died in St. Petersburg, where he lived the final three years of his life.

As part of a collaborative concert with Nitty Gritty Dirt Band founder John McEuen, Amram will perform a multi-instrumental stew of songs and stories about Kerouac at the Palladium on Friday. On Saturday, Amram will appear at The Flamingo Sports Bar, the author’s favorite and the site of a twice-yearly Jack Kerouac Night — on his birthday and on the day of his death in 1969.

For Amram, it is a homecoming. He lived in the St. Petersburg area for one year, attending first grade at Sunshine Elementary School in Pass-a-Grille. More importantly, though, it is a way to honor his friend.

The two met during a “bring your own bottle” party at a painter’s loft in the New York City while they were struggling artists.

“There was no doorman or list or velvet rope at those parties,” Amram said. “Anyone could go.”

David Amram

Amram had never heard of Kerouac, but the now-iconic author had apparently seen him perform at local jazz clubs. Kerouac, wearing a thick lumberjack’s jacket, introduced himself as a writer and asked if Amram would play music for him while he read one of his works.

“There was no piano but I had a French horn,” said Amram, who also is skilled with flutes, whistles and percussion. “We just clicked. Then when we were done, he ran off and danced the rest of the night with some young lady.”

Their initial meeting was short but enough to kindle a friendship.

***

Kerouac would visit Amram at his sixth floor walkup on 38th Street, where they would discuss their common dreams of one day getting married to “nice girls” and settling down in a small town somewhere — or of their mutual admiration for French. Kerouac was French Canadian and Amram’s mother taught the language.

Most of all, they bonded over their love of jazz and poetry.

Their impromptu public performances became a regular occurrence in New York City, and everywhere was a potential venue — parties, bars, park benches. There was no schedule. If they bumped into one another in public, if Amram had an instrument handy, if they were in the mood, they went to it.

“On The Road” was released in September 1957, and in the years that followed it turned Kerouac into the voice of his generation. But before his fame peaked, he and Amram provided artists in the city with a new creative outlet.

Friends clamored for the two to put on a scheduled show. In fall 1957, they obliged by performing at the Brata Art Gallery — an event credited as the first official public collaboration of jazz and poetry in New York City.

Kerouac’s fame as author, performer and the man who coined the term “Beat Generation” soon took him around the world. Still, he continued to choose Amram as his musical partner.

Amram scored “Pull my Daisy,” a short film adapted from a Kerouac play and narrated by the author. And they continued to perform as a duo whenever Kerouac was in New York and the mood struck them.

Amram went on to enjoy a distinguished career. He was named The New York Philharmonic’s first composer-in-residence in 1966. He worked alongside such legends as Willie Nelson, Dizzie Gillespie, Tito Puente and Bob Dylan. He recorded more than a dozen jazz albums as a leader, close to 40 as a sideman, and wrote scores for such films as “Splendor in The Grass” and “The Manchurian Candidate.”

At 82, he continues to perform. Kerouac’s career, while illustrious, ended much sooner.

***

The author relocated to St. Petersburg with his mother and third wife in 1966, perhaps finally fulfilling the dream he shared with Amram of settling in a small town.

One of Kerouac’s haunts was Haslam’s Bookstore, where he is said to have visited to drink coffee, talk literature, and make sure his books got prominent display.

“I always laugh when I hear that story,” said Amram. “Most authors will try to do it, but I hear Jack did it every time he was there.”

One of Kerouac’s other pastimes was drinking.

He drank at the Flamingo as Oct. 20 turned to Oct. 21. He returned to his home at 5169 10th Ave. N. shortly after midnight. At 3 a.m., he was taken to St. Anthony’s Hospital, where he died of internal hemorrhaging from cirrhosis of the liver. He was 47.

Asked why his friend drank himself to death, Amram listed a few popular theories: Kerouac never enjoyed fame; he hated that people cared more about him as a celebrity than as an author, and that despite his reputation as a free spirit he was conservative in his beliefs and fit poorly into the wild atmosphere of the ’60s.

Still, Amram claims no special knowledge.

“I would never dare to pretend to know what was going on inside another man’s head and neither should anyone else,” he said.

Amram does wonder how Kerouac’s life would have turned out had he tried rehabilitation. His friend, Amram said, was a spiritual man and would have embraced the process.

“I think he would be alive to participate in these celebrations. I think he would be on stage with me, his bongos in his hand and singing.

“I still miss him.”

Leave a Reply