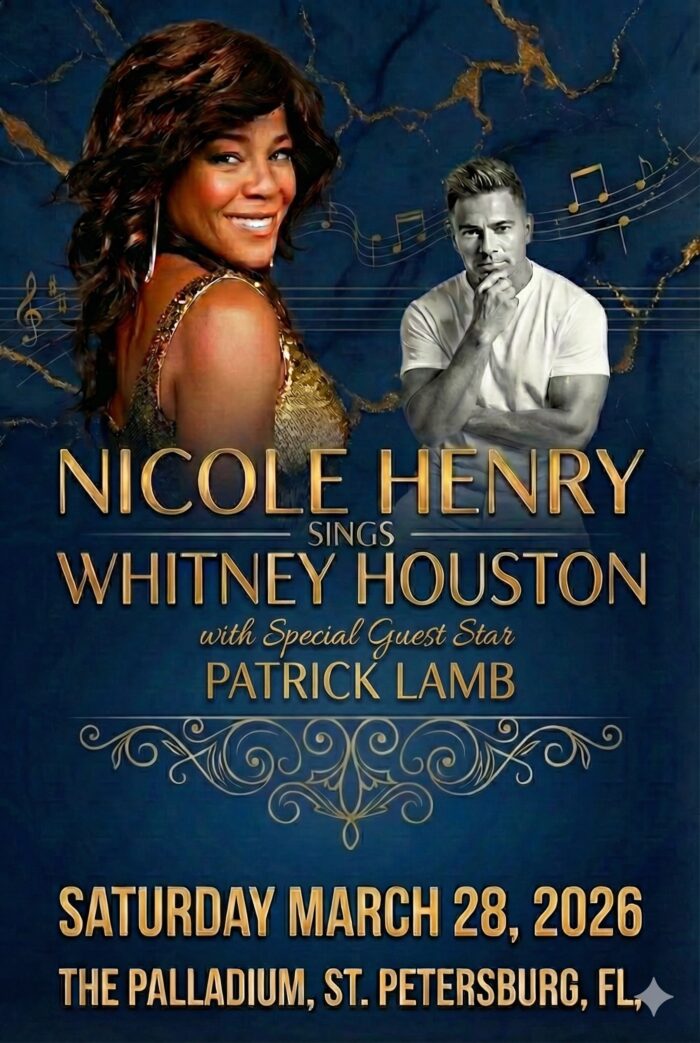

One of my dreams for the Palladium is that we’d be the site of a Florida Orchestra Masterworks concert. This Saturday, March 24, that dream is coming to fruition when the orchestra takes the stage to perform a program that includes the music of Mozart, Haydn and Schubert.

Tickets are almost gone, so call the orchestra box office or follow this link for on-line tickets.

I’ve been a TFO fanatic since my college days at the University of South Florida, when my friends and I would sneak into McKay Auditorium at intermission since we were too broke to buy a ticket. In those days, the orchestra set out flutes of champagne at intermission. We’d swallow some champagne then sit in the seats of the south Tampa ladies who had come to be seen in their best outfits, but always left at intermission.

The orchestra was known as the Gulf Coast Symphony at that time and it was conducted by Irwin Hoffman, a man with the imposing presence and aristocratic air of a true Maestro. He set a very high standard for his regional orchestra, a standard has remained in place as the Gulf Coast Symphony grew into The Florida Orchestra.

Hoffman died on Monday at age 93. Kurt Loft, the longtime music critic of the Tampa Tribune, has written a lovely memorial that appears on the TFO website. Follow this link to the TFO site or read an excerpt here:

BY KURT LOFT

March 21, 2018

In the summer of 1981, I had the privilege of an invitation for lunch at the St. Petersburg home of Irwin Hoffman and Esther Glazer.

It was a hot day, and soon after greeting me at the door, the couple offered a pitcher of lemonade and sandwiches ─ and a genuine curiosity about the 25-year-old journalist sitting in their living room.

Hoffman was gracious. He answered my questions with eloquence, and paused while I scribbled notes in my reporter’s pad. Glazer, his violinist wife, talked about their talented musical children: composer and pianist Joel, cellist Gary, violist Toby, and harpist Deborah.

The couple also was proud of their spacious house off the water, and eager to share its most prized possession: an original score by Georg Philipp Telemann, protected under glass like a museum relic.

As we strolled and chatted, I realized Hoffman wasn’t the imposing maestro who would tower over The Florida Orchestra for two decades, bringing Beethoven or Tchaikovsky to life with a sweep of his hand ─ always without a baton. Could this be the same man who made his conducting debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra at age 17? Was this the prodigy of the famed conductor Serge Koussevitzky, and who later became music director of orchestras in Canada, the United States, and South and Central America?

Irwin Hoffman

Adding a poignant moment to TFO’s 50th anniversary season, news of Hoffman’s death on Monday (March 19) at age 93 gave way to memories of the years I knew him, mostly through dozens of interviews during my time at the Tampa Tribune. Those conversations tapered off in 1988, when Hoffman stepped down as music director and Jahja Ling stepped in.

The orchestra has seen three music directors since Hoffman left, and audiences, musicians, and critics all had their opinions about who was best or a favorite. Most seem to agree that Hoffman was a dead-serious musician who helped shape the orchestra into what is today.

“This orchestra owes everything to him,’’ said Don Owen, former principal trumpet who played with the group for nearly 45 years, when it was the Florida Gulf Coast Symphony and before that, the Tampa Philharmonic. “He put us on the road to success.’’

Toula Mahalas Bonie, a violinist who played many years under Hoffman’s leadership, said he raised the musical bar for anyone willing to accept him: “Hoffman motivated every person to play his best. To this day, I remember every moment that molded me into a better musician and person.’’

Another orchestra veteran who played as a percussionist from 1973-78 called Hoffman one of the biggest influences in his life. He was a musical titan, said John Bannon, who returned to TFO in 1988 as principal timpanist.

“Irwin had command as a conductor that I’ve never seen surpassed, both in terms of his craft and in general musicality,’’ he said. “I have always believed there is a culture of performance excellence in The Florida Orchestra, and it is Irwin who established that culture. I have great respect and appreciation for every one of his successors here, but they have built on the strong foundation laid by Irwin.’’

Brian Moorhead, who recently retired from his chair as principal clarinet, once said Hoffman’s ear for the 4/4 beat in a Strauss waltz was nothing short of magical. Over the years, other musicians praised Hoffman’s economy of movement at the podium ─ one hand guiding the music, the other holding onto his lapel ─ as well as his remarkable memory, which allowed him to work without a score in concert.

As a programmer of music, Hoffman mixed up each season, playing traditional and not-so traditional works. In retrospect, he gave considerable weight to 20th-century and contemporary composers ─ often stoking the ire of listeners. He scoffed when a group of patrons signed a petition to ban Stravinsky and Prokofiev from orchestra programs. When he conducted one of the Bartok violin concertos in the mid-1980s, with Esther as soloist, some listeners walked out of the hall. The performance, however, received national attention from critics who flew to Tampa for the occasion.

Like many brilliant conductors, Hoffman could be a difficult personality, especially in rehearsal. Bannon remembers him as “tough and scary,’’ but motivated by the discomfort of those moments. It was a small price to pay for what the man gave back to the orchestra, said Owen.

“He was a completely irascible dude,’’ he said. “None of us got along with him, but we weren’t there to love him, or for him to love us.’’

The orchestra will dedicate this weekend’s concerts of A Little Night Music to Maestro Hoffman.

‘He brought out the best in us’

More TFO musicians past and present remembered the colorful maestro:

Bill Mickelsen, principal tuba: It was 1979, my first season in the orchestra. I was a complete newbie, and eager to show the Maestro how beautifully I could play the tuba. We were rehearsing Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks, a tone poem by Richard Strauss depicting a folk hero of the German Middle Ages who allegedly played many tricks making fun of those in authority.

There are numerous “mini-solos” for the tuba sprinkled throughout this marvelous work, and one near the outset involves a soft and expressive passage, concluding in a flippant little arpeggio ending on a high note. I had worked very hard to play this particular passage smoothly and with great finesse, and it came out flawlessly at rehearsal.

Immediately Maestro Hoffman stopped the rehearsal with a cut-off gesture. There was complete silence as he looked over at me and said, quite sternly, “Mr. Mickelsen, that was very tastefully played. However, Till Eulenspiegel was an unsavory character, so please, just play that passage in a more rustic manner.” Then Don Owen, our beloved but outspoken principal trumpet, says “Yeah, Bill, just poop it out.” The entire orchestra cracked up, and I was a bit embarrassed, but from then on I always tried to play in a style appropriate to the story line.

Teri Denton, TFO musician 1977-1984: I had the distinct privilege of sitting as acting principal cellist under Maestro Hoffman. He had a unique manner in which he related to us as orchestra members. He was a very serious and gifted conductor — that was clear to all — however, as my position was literally under his arms as he conducted, I saw on more than one occasion a warmth and mischievous side to him. I really don’t know if any of the other musicians ever observed that side of him. I did.

He brought out the best in us as players. He knew what he wanted the music to sound and feel like. He was relentless in pursuit of the standard he desired. I am forever grateful for his adherence to strict professionalism as he took to the podium. He made me a better musician and the orchestra benefited greatly under his leadership.

Leave a Reply