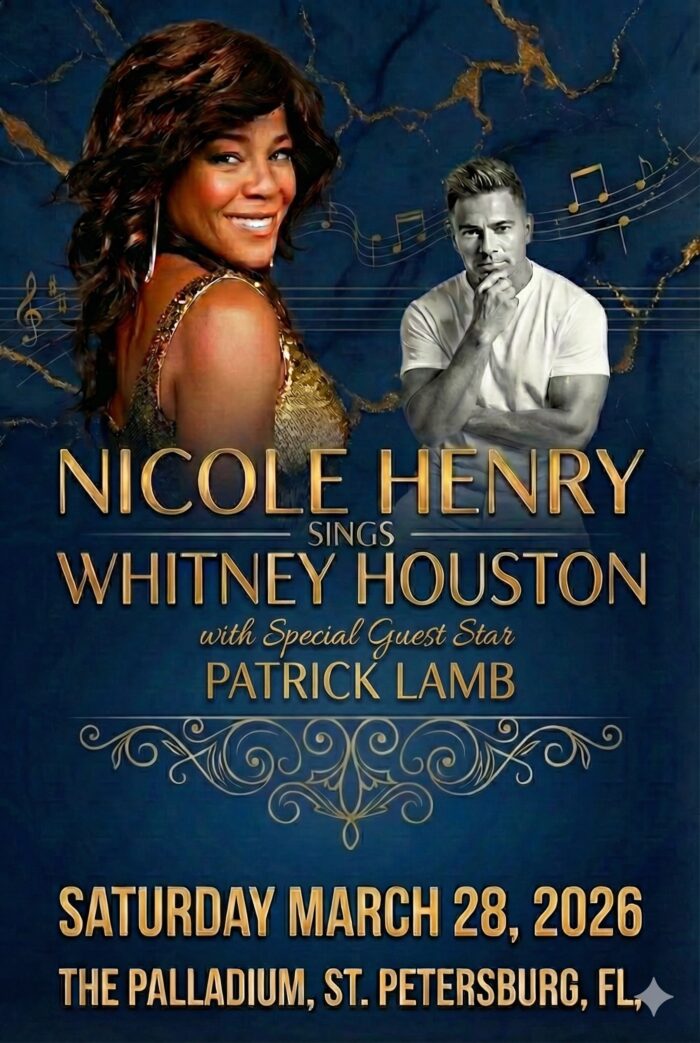

I hope you can join me Wednesday night at 7:30 when the Palladium Chamber Players return to our main stage with another stirring musical adventure.

This time Artistic Director Jeffrey Multer has created a program featuring Mozart, Rachmaninoff and Schumann. And our regular players – Multer, Park, Arron and Farina – will be joined for the Schumann Quintet For Piano and Strings, Op. 44, by the Florida Orchestra’s Nancy Chang.

Tickets are available in person or by calling our box office at 727-822-3590. For on-line tickets, just follow this link.

My former colleague, Kurt Loft, a veteran music journalist, is again writing program notes for our series. His notes will appear in the program Wednesday night, but you can get an advance look right here in the Palladium Paul blog.

Program Notes for Palladium Chamber Players, Wednesday, March 14.

By Kurt Loft

Like a memorable dinner, a chamber music recital needs the right ingredients. The menu requires contrast as well as harmony, a full serving of this, and a sprinkle of that.

The Palladium Chamber Players specialize in appetizing programs, carefully selecting what composers and pieces will carry the night and satisfy listeners. Tonight’s lineup of works by Mozart, Rachmaninoff and Schumann underscores the thought that goes into every season and performance.

Kurt Loft

“When we sit down to do our programming, we first look at what music goes well together, but what doesn’t all sound the same,’’ said Jeffrey Multer, the group’s violinist and concertmaster with The Florida Orchestra. “We look at contrasts in style, period, and ensemble combinations. And performing the music requires an energy and commitment that audiences can respond to.’’

The group’s latest program highlights masterpieces from three different centuries, all easy on the ears but demanding to play. Each work stands alone, but is somehow connected.

“It’s tricky,’’ Multer said. “You have to know the music well enough so that one piece flows into the other, but you have to avoid any redundancy. You don’t want the same sauce for everything.’’

So, let’s dig into what you’re about to hear …

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) ─ Duo for Violin and Viola, K. 424

Mozart never hired a public relations firm to flaunt his talents, but by the time batches of his 626 published compositions began trickling through Europe, his reputation was set in stone.

Part of Mozart’s genius – and charm – was the innocence and simplicity of so much of his output, although as a musician, Mozart was anything but innocent. Nor was he simple. Mozart could arrest our senses through his operas, symphonies, concertos and string quartets, but with the Duo for Violin and Viola in B Flat Major, he impresses with something as modest as a pair of fiddles.

“This is such a perfect piece and it’s unbelievable what he gets out of two instruments,’’ Multer said. “It’s like what T.S. Eliot said about squeezing the universe into a ball.’’

Danielle Farina

The Duo unfolds in three contrasting movements: a slow opening, graceful middle section, and a set of ascending and descending variations to close. Mozart creates a more complex counterpoint than actually exists, with lots of double stops and 16th notes, carefully placing each voice in such tight sequence that listeners can close their eyes and believe they’re hearing a trio or even a quartet.

As a whole, this music is tasteful, poised, and sweetly lyrical. Violin and viola are equals ─ one seldom outshines the other. Even when the violin takes center stage, the viola provides such rich harmonies that no one can argue over who’s in charge.

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) ─ Sonata in G Minor for Piano and Cello, Op. 19

Few musicians struggled with public criticism as much as Sergei Rachmaninoff. After the disastrous 1897 premiere of his First Symphony, of which a poor performance by the orchestra was partly to blame, he sunk into despair. A fellow Russian composer and critic, Cesar Cui, called the new work a “symphony from Hell,’’ a review that shattered the overly sensitive Rachmaninoff.

Under a cloud of depression, he stopped writing music for nearly three years. He eventually sought medical help, and immersed himself in therapeutic hypnosis, gaining enough confidence to write his now-famous Second Piano Concerto and the Sonata for Cello and Piano in G Minor ─ the centerpiece for tonight’s program.

Jeffrey Multer

The work has been described as a piano sonata with cello accompaniment, as the piano can easily dominate its less dynamic sounding companion. Considering that Rachmaninoff was a powerful and virtuosic pianist with huge hands ─ he could span a 12th, or an octave and a half ─ we might understand a bias toward his chosen instrument. But a good performance should reveal an equal conversation between the two performers as they strive for complementary tones and colors through all four movements.

The Sonata serves as a microcosm of Rachmaninoff’s trademark style: an atmosphere of melancholy and nostalgia, soaring melodies that touch on pathos, and brilliant instrumental writing. Listeners familiar with Rachmaninoff’s works might hear nascent echoes of the Second Symphony and “Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini.’’

Piano and cello exchange and elaborate on two themes in the opening movement, which begins slowly and leads into a skirmish for the cello in the following allegro scherzando, where both instruments drive into a dramatic climax. The third movement is the heart of the work, an introspective, impassioned plea and one of the composer’s most inspired creations. The finale dispels the earlier mood as both instruments embrace a vibrant, optimistic theme, tossing it back and forth, re-creating a six-note motif from the opening movement, and then closing with a flourish.

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) ─ Quintet for Piano and Strings, Op. 44

Schumann was a visionary who helped define musical romanticism by, in his own words, sending “light into the depths of the human heart.” A superb pianist, literary critic and advocate for such up-and-coming talents as Brahms and Chopin, Schumann kept up a busy life, and his marriage to Clara Wieck stands as one of the more poignant love affairs in the world of art.

As we look at Schumann’s career, his compositions can be set up in chapters, following his habit of writing in one medium at a time: chamber music one year, symphonies the next, and entire seasons devoted to songs or church music. In 1842 alone, he wrote three string quartets, a piano trio and the magnificent Quintet for Piano and Strings, essentially inventing a new musical medium: a piano embedded into a string quartet (Schubert’s earlier “Trout’’ Quintet employs a double bass rather than cello).

Schumann sketched the work in less than a week, and his apparent ease in composing comes through in the explosive opening moments. After all members of the party announce a scintillating theme, they settle down into individual personalities. They borrow each other’s ideas, repeat a beautiful cantilina melody, and sing in unison until the close. Schumann turns darker in the second movement, introducing a funeral march in the solemn key of C minor. Violin and cello play an impassioned duet before giving way to a moment of anguish.

The urgent-sounding scherzo borrows a theme from Schumann’s “Ten Impromptus on a Theme of Clara Wieck,’’ (he dedicated the Quintet to her) and the crowning finale harks back to the opening of it all, topped off by a double fugue worthy of Bach.

Leave a Reply